Francis Morland – Sculptor and Drug Smuggler

8. 9. 2013 // Stewart Home // Kategorie Randnotizen 2013

Francis Morland (b. 1934) is a now largely forgotten British sculptor who was well connected into the London art world of the 1960s and totally estranged from it after 1970. Writing about Morland’s contribution to The New Generation 1966 at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in Studio International, P. Procktor announced:

Comparing the new work with the old there can be few transformations of style more radical. The break is complete. These large entwining serpentine shapes relate to the work of other sculptors in this idiom, speak in a sculptural language which is familiar because it is to a certain extent a shared language. What interests me is not the grammatical principles of the language nor who invented them, one can safely assume that Morland did not, but what this language is used to say. Kiss, the only title of the four pieces in the exhibition which has a specific human connotation, provides a clue to all. The twisting and entwining shapes are metaphors of the body, headless, limbless, featureless, but miming the poses of relaxation or sexual intercourse like gigantic strings of macaroni… (P. Procktor, “The New Generation”, Studio International, July 1966, pp. 5-11.)

Morland can also be seen in Gerald Laing’s photograph London Artists in Paris (1963), which was taken during the Paris Biennale des Jeunes. A number of those in the picture are now rather famous: David Hockney, Joe Tilson, Peter Blake, Allen Jones, Derek Boshier. 1963 was a key year for Morland since he moved from working in bronze to using fibreglass finished in coats of cellulose paint.

Morland was well supported by the UK state funded arts system in the sixties in terms exhibitions, purchases and teaching. He was a modest success but he completely disappeared at the beginning of the seventies. Morland, graduated from the Slade School of Fine Art in 1956 and taught in sculpture department at St Martin’s School of Art from 1963 until the mid-sixties. His mother, Dorothy Morland, had been director of the Institute of Contemporary Arts. Morland’s work in bronze of the early sixties was well received. An anonymous Times critic covering the Sculptors of Today exhibition at the Bear Lane Gallery in Oxford praised him for ‘distinguished modelling coupled with imaginative insight’ (The Times, 11 May 1962).

1966 was to prove another turning point in Morland’s life, since this was then that he secured an introduction to Damien Enright. Enright is now a respected Irish journalist, but as detailed in his autobiography Dope In The Age Of Innocence, in the mid-sixties Enright was a notorious drug smuggler. Morland and Enright were introduced to each other by Tina Lawson. Lawson was Morland’s babysitter (and later the wife of English Situationist International member and international dope dealer Charlie Radcliffe). At this time Morland and his friends knew nothing of drug scamming but soon some of them became major players though the fortuitous combination of their money and Enright’s contacts (for which Damien was paid a percentage). Morland was an ex-public school smoothie, a former ski champion, belonged to the fast set clustered around Princess Margaret, and was the heir to the Somerset Morland wool ‘fortune’ (actually the family business went belly up in the seventies, and this much envied ‘legacy’ disappeared into the hands of the receiver).

Morland was unable to support himself from the sale of his work, and keen to find alternative sources of income. Once he gatecrashed the drug scamming game, he realised that one of the ways he might smuggle hash was to seal it inside his large fibreglass sculptures, a hole which could be replugged was all that was required to get the dope in and out of his art works. To Morland smuggling was a means of subsidising his real passion, making art. In the late sixties Morland’s work appeared in group shows such as New British Sculpture organised by the Arnolfini Gallery at outdoor locations in Bristol and the 1st Burleighfield Sculpture Exhibition at Burleighfield House, Loudwater, Bucks (both 1968). Morland’s one person show Recent Sculpture opened on 12 September 1969 at the Axiom Gallery, London W1. Under the headline “Hinged and Unhinged”, Guy Brett dismissed it as ‘decorative’ in a Times review of 19 September 1969.

Morland’s first bust occurred in October 1969, hot on the heels of his Axiom exhibition. The art world reacted with horror, seeing taking drugs as one thing and smuggling them as quite another. Morland’s career as a professional sculptor came to an abrupt halt, and he was dropped by many of his professional friends. The charges against him took some time to wend their way to a conclusion in the courts but The Times dutifully covered this on 23 March 1971 under the heading “Diplomats In Drug Ring, Crown Says”. Morland skipped the country while on bail so he wasn’t actually up before the beak. Others not present were a Mr Khaled and Fulton Dunbar, Third Secretary at the Liberian Embassy in Rome. Morland and Dunbar were said to have made statements admitting their guilt and that of others.

Morland’s partner Keith Wilkinson pleaded not guilty and so was tried separately. It was claimed the gang smuggled £150,000 worth of cannabis into the UK, and had plans to ship a lot more around the world. In the dock was Robert Paul Palacios who used his catamaran to transport the drugs from Morocco to Cowes, on the Isle of Wight, from where he drove them to London in a Rolls-Royce car. Palacios who’d been hired to do the job by Morland was fined £4000. Morland’s wife Susan was said to be only on the fringe of the gang and was fined £500 for possession of cannabis and cannabis resin. Police surveillance of Morland and Palacios and aspects of the court case are covered in Adam’s Tale by Gordon Honeycombe (Hutchinson, London 1974 – the ghosted written memoirs of Adam Acworth, a London drug squad detective).

Morland began his first jail sentence for smuggling in America. After sailing his 47 foot ketch loaded with hash from Morocco to the US in July 1971 and being caught upon entry, he was jailed for eight years and fined $15,000. The Times tersely covered Morland’s second bust on 4 June 1972 under the headline “London Man Jailed in US Drug Case”. After doing time for his first two ‘crimes’, Morland was next nicked attempting to land cannabis worth £3.5 million in northern Scotland. When he was jailed for nine years and had assets of more than £232,000 confiscated, The Times of 25 June 1991 covered the case under the headline “Drug Smuggler – Francis Morland”.

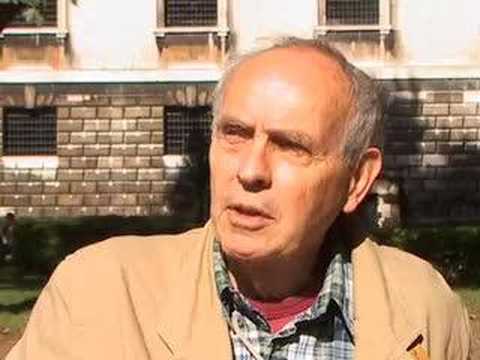

Unfortunately this 1989 bust was not his last, nor did the 1991 judgement result in his final stiff sentence. When I tracked Morland down in 2005 because I wanted to include his work in my Hallucination Generation exhibition at the Arnolfini in Bristol, Morland was once again in jail for drug smuggling – but at the same time using day release from jail to work with a potter and make ceramic sculptures. I interviewed Morland on camera about the 1950s and 1960s London art and drug worlds in 2006, and you can see that encounter here.