THE GREATEST CRIME OF ART IS TO PRETEND TO DO POLITICS

12. 7. 2012 // John Jordan // Kategorie Randnotizen 2012

Last Saturday a wonderfully audacious action took place at Londons Tate Modern museum over 100 people installed a 1.5 tonne wind turbine blade in the museum, without asking permission of course! It was the latest in a series of actions that have taken place against the sponsorship of the Tate by oil giant BP by Liberate Tate an art activist group that was born from the workshop that we The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination held at Tate Modern itself.

It was the fear by the institution of the museum, of artists not just talking and representing action but actually taking disobedient action that created the rich ground from which Liberate Tate was born.

What is it about the word disobedience that the institutional art world doesnt understand? In the autumn of 2009 the Nikolaj Contemporary Art Centre Copenhagen dropped the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imaginations (Lab of ii) bike bloc project when they realised that the tools of civil disobedience that we were going to build were not gestures but actual tools and tactics for the protest actions around the UN climate summit. The curator told us that she feared that the museums funders, the City of Copenhagen, would not support any illegal activity. It seemed that she had assumed we would pretend to do politics.

Fast forward to winter 2010 and another international contemporary art museum, not in a converted church this time, but a transformed power station, Londons Tate Modern. The Lab of ii had been invited by Public Programs to run a two day workshop on art activism, looking at the issues of the museums environmental impact and exploring, in their words, the question: What is the most appropriate way to approach political issues within a publicly funded institution? After several months of planning, we received an email from the curators that casually ended with the paragraph: Ultimately, it is also important to be aware that we cannot host any activism directed against Tate and its sponsors, however we very much welcome and encourage a debate and reflection on the relationship between art and activism.

There were two things we could have done in response. We could have refused to run the event under such draconian criteria and pulled out, or we could do something much more interesting, keep stum and make the email the primary material for the workshop. At the end of the final planning meeting, at which it was confirmed that the workshop would conclude with a public intervention, one of the curators, lets call her Sophie, excitedly announced that it was incredible that it took the Tate till 2010 to work with a real activist. I walked out of the meeting feeling slightly sick but convinced that the strategy of using the text from the email could form the basis of a fascinating experiment in radical pedagogy.

Entitled DISOBEDIENCE MAKES HISTORY: Exploring creative resistance at the boundaries between art and life, the workshop was promoted on the Tate websites front page and soon sold out. On a chilly January Saturday morning, myself, thirty three participants and sophie the curator, sat in a circle on the top floor of the museum and began the first day long event. All was going well as we played games to build conviviality, discussed our personal acts of disobedience against injustice, learnt consensus decision making techniques and explored the work of artists who had applied their creativity to acts of civil disobedience ranging from Gustave Courbet to Sylvia Pankhurst. When I began to talk about the climate crisis and the context of the Tate, mentioning the fact that British Petroleum was a major sponsor with its ex CEO, John Browne head of the board of trustees, things started to turn. When I projected the email on the wall and asked the students to stand along a spectrum line to begin to open up discussion as to whether we should or shouldnt obey the demand from the Tate, the shit began to hit the fan.

The curator, tried to sabotage the process of discussion, claiming it was limiting the participants experience. The participants were thrown into heated debate, after several hours two thirds of the group decided to plan an intervention at the Tate the following week targeting the sponsors and highlighting issues of censorship. Leaving the Tate that evening Sophie was clearly upset: you betrayed our trust she told me, we are going to have to have a meeting before next Saturdays workshop. When I got home one of the participants had emailed: thanks again for a great day, very inspired by this liberating experience I’ve never been to a workshop that raised pulses and adrenalin the way this does.

The following Friday, I was summoned to the Tate to discuss the planned intervention. Four people welcomed me: Sophie; another curator, Michael; a woman who never smiled and whose name escaped me, head of visitor services and David, head of safety and security. They asked me what was going to happen and I told them that I knew as much as they did, that following the Labo of iis methodology the workshop was now entirely self managed by the participants and the intervention would be designed by them during the final workshop. David explained in no uncertain terms that there were three principles paramount to the Tate: The safety of people, the protection of art works and finally, to ensure the quiet enjoyment of the public. That goes without saying I replied, no action we take would ever hurt anybody or any thing. In fact all our work is precisely about minimising the damage our system has on people and eco systems.

Then things became interesting. He began to talk about Reputational Risk, about the fact that an action could affect a funding deal, that the Tate prided itself on free access to art and that if their funding was hit it would not be a positive thing for anyone. I looked everyone in the eye and asked whether they were censoring the workshop, Censorship, thats an emotive word to use. was the reply. The tense and frank meeting lasted over an hour and a half, we talked about BPs use of the museum to give it a social license to operate and about the fact that the sponsors should not be embarrassed. We dont have any problem with the intellectual content Micheal told me and then proceeded to announce that three of them would be present at the next workshop and would desist any activity that was not commensurate with the Tates mission.

As I left, refusing to toe the line, David leant across the table We have done much riskier things .. Ive had meeting like this with Damien Hurst and Sarah Lucas. Yes I retorted smiling they never bite the hand the feeds them do they. In fact they FEED the hand. As soon as I got home, I wrote up the discussion and put it online for workshop participants to see, more great material.

The next morning the participants arrived even more enraged than before, the more the Tate tried to shut things down, the more the students were learning about how corporations drape themselves with the cosy cloak of cultural legitimacy and how those who work in our (co called) public institutions play the game. They experienced first hand the hypocracy of cultural institutions that claim to be sites of progressive practices and with every exchange with the curators they became more radicalised. Eight hours later, the workshop ended with a simple, the words ART NOT OIL were placed in the windows of the top floor.

But thanks to the Tates cack handed attempts at censorship, the participants set up Liberate Tate and have brought the issues out into the public arena in a way that when we were sitting in that room fighting with the curators we could not have anticipated..

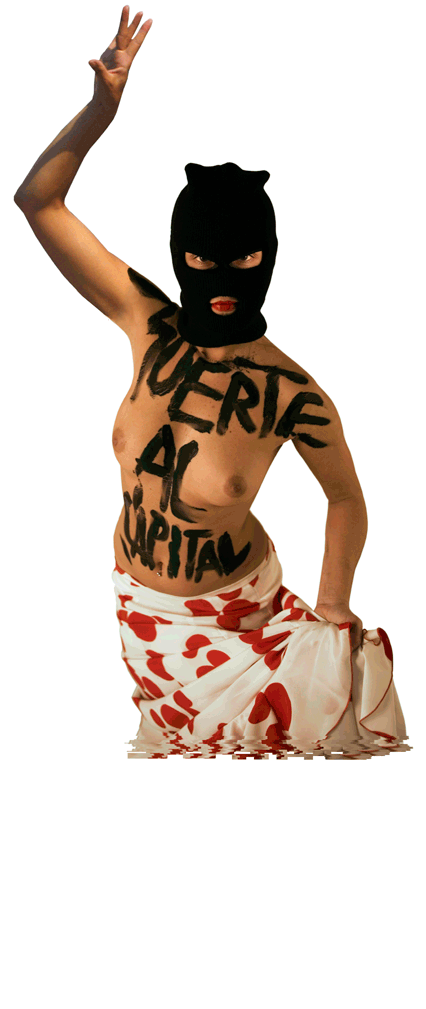

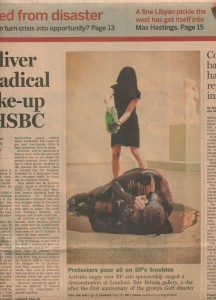

Liberate Tate has disrupted the BP summer party held at the museum- with lots of molasses poured inside and outside the gallery: We have sent dead birds and fish into the roof of the Tate – which that had to be shot down by security; we made giant sunflowers in oil on the floor and covered a naked body in black crude. Most of these actions got extensive media coverage, including front page news such as the Financial Times. In the end the DISOBEDIENCE MAKES HISTORY workshop was a pedagogic success beyond anything we could have ever imagined, thanks to attempts to make us pretend to do politics.

Last weeks The Gift took the disobedient creativity one step further. (see this great video about it ) A British law states that members of the public can donate an art work to a museum and the museum have to consider it for their collection. So Liberate Tate decided to donate a a gift that would be hard to ignore, brought across the city by 100 people, pushed through security and deposited on the floor of the museum with grace and audacity. The communiqué sent with the work ended: “What we have brought you is the blade of an old wind turbine, sixteen and a half metres long, beautifully sharpened by the weather. It is a blade to cut the unhealthy umbilical cord that connects culture with oil, a blade that reminds us that when crisis comes, when the winds blow strong, the best thing to do is not to build another wall but raise a windmill

Last night one of the many small groups of invisible hands that rest on the keyboards of computers manipulating our society with their magic numbers and occult equations,

Last night one of the many small groups of invisible hands that rest on the keyboards of computers manipulating our society with their magic numbers and occult equations,