220 names and some questions about the silence around them

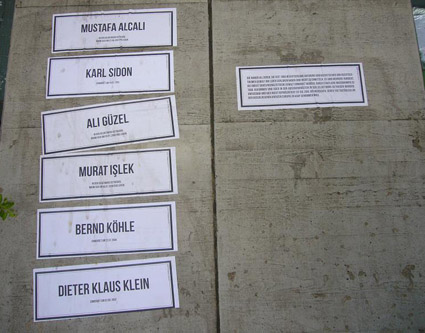

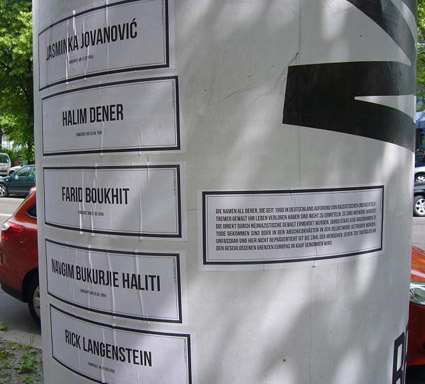

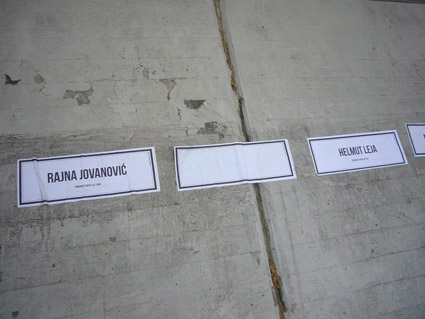

9. 6. 2012 // Federico Geller // Kategorie Randnotizen 2012From last week an intervention in the walls of several neighborhoods of Berlin recalls the names of more than 220 victims of neonazism and racism between 1990 and 2012.

The names are printed in strips in a very sober manner, that remind newspaper obituaries, with the dates the victims were killed. There are many Turkish names and also some African, Kurdish, Italian and Vietnamese. But there are also some German homeless people and a few antifascist activists, like Silvio Meier. A few strips have no names at all and others have a statement in Turkish, German or English that explains the limitations of the list:

The names of all those who have lost their lives in Germany since 1990 due to extreme right wing and racist violence cannot be ascertained.

There are many hundreds who were murdered directly by neo-Nazi violence or killed due to State policies, or who committed suicide in deportation jails.

The number of people who lose their lives every day on the closed borders of Europe are unable to be grasped and are not represented here.

The context of this action made by a Plakat Group are the crimes of the NSU (Nationalsozialistischen Untergrunds) which came to light last year. But explaining which crimes are not included, an invitation to look for a broader context is clearly set.

On Saturday 3rd June I went to an open hearing in the Akademie der Künst, organized by a coalition of antiracist and antifascist social organizations: Schweigen und Verschweigen: NSU, Rassismus und die Stille im Land ( Silence and Concealment: NSU, Racism and Quietness in the Country).

In one panel of the discussion, three researchers on extreme right organizations -David Begrich, Ulli Jentsch and Kati Lang- made complementary suggestions towards a better understanding of the extreme right phenomenon . All of them expressed their shared skepticism on the official investigations of NSU crimes, based in many facts: there is a lot of information kept in secrecy and the only one that has been published come from official sources; there were at least five informers of the secret police infiltrated in the NSU net for ten years; there are significant qualitative and quantitative differences between official and independent reports on neonazis activities and so on. To these factors, they added the confirmation of structural obstacles in the police forces like institutional racism and bureaucratic inertia. And beyond these particular institution, the ever-present noise of the media who echoed in loudspeakers the version in which the victims of the NSU, mostly Turkish, were killed by foreign mafias. They labeled these crimes, committed between 2000 and 2007, Dönner Murders.

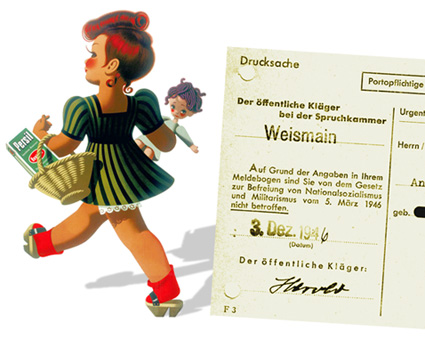

A ring of mystery and secrecy around the untouchable personifications of power and their servants is not a German state singularity. It´s a sort of publicized black box we can find everywhere, a border between the legal and illegal use of force that remains obscure, serving as a continuous and renovated mechanism of dissuasion. But in everyplace there is a particular history with its proper weight and potentialities, where the no go areas of the unknown amplify different ghosts, some newer some older. So it was no surprise when someone in the public asked the experts whether there is a nazi Geist (spirit) in the police. The question remained floating over the audience just some seconds like a soap bubble with the name of a detergent, Persil. The term was widely used as a nickname for the compulsory statements during postwar denazification. In those days every German and Austrian had to fill the Persilscheine to inform the new authorities of the American zone, which had been his/her degree of involvement in the Nazi regime.

Just as the intervention in the walls of the Plakat Group, the year 1992 appeared in many voices of the hearing as a landmark, as the beginning of the present timespan of racist actions. In that year, according to a Interior Ministry report, there were 2,277 racist attacks, that included a fire on a Turkish family house where three people died. We must understand the 90s if we want to know whats happening now said David Begrich (Network for Democracy and World Openness in Sachsen), who considers that neonazism is not a constellation of separated phenomena of youth rebellion and isolated extreme right organizations, but a movement, that changes names very often and its defined by two characteristics: 1) It fights for free space for its activities and 2) engages in different ways of violence. Whenever a Nazi is allowed to speak, he is silencing others he concluded.

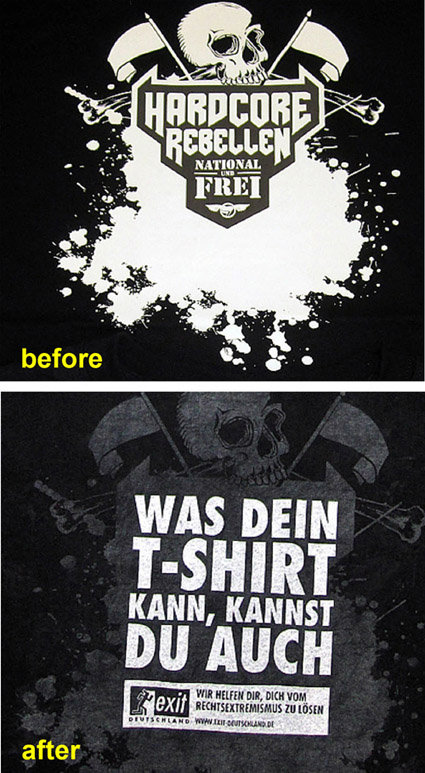

Ulli Jentsch, from the Antifascist Press Archive and Education Center of Berlin, made focus in the fact that the tree neonazis of the NSU (two of them were found death last November) could not act for years in clandestinity by themselves. They needed a net to provide them with money, contacts, documents and other resources. He also insisted pointing out the conditions and social environment in which their identities developped, and the role of demos, racist attacks, concerts and a particular long campaign against an exhibition about the war crimes of the Wehrmacht (the German regular army). The exhibition was shown in several cities of Germany between 1995-1999 and 2001-2004 and triggered the anger of nationalist who keep insisting that the Holocaust was done by the SS, meanwhile the Wehrmacht kept its honor respecting the traditional rules of combat I see more memory bubbles. This time they recall a very original intervention made in 2011 by Exit-Deutschland. They sent 250 t-shirts as a present to the organization team of the concert Rock für Deutschland, which was an initiative of the nationalist party NPD in Thüringen. The t-shirts had the image of a skull and the sentence Hardcore rebel: national and free. But when they were washed the whole design was gone and a new message appeared: what your t-shirt can do you also can. We help you to leave right wing extremism. www.exit-deutschland.de.

Kati Lang, from the office for assisting victims in the organization RAA Sachsen, talking about the authorities, insisted on calling the ideologies they preserve with their proper names, meaning racism and social Darwinism. She told that Police keep using the word race in their reports and that it shows quite a higher sensitivity to left wing extremism than to right wing one. She finds exhausting attempting to dialog with authorities that dont want to and neither want to change: any critic against the government is immediately identified as an attack against democracy. The audience clearly supported her words when she stated that it was obvious that the secret police is not the right tool to combat neonazism. And the final questions she shared were: 1) Are we underestimating right wing terrorism? 2) how do we deal with it?

Just before the end of the panel, somebody in the public took the micro and said the whole problem is quite wider: we havent still responded the Sarrazin scandal.

(to be continued)